Grazing-Incidence X-ray Fluorescence:

Achieving Monolayer Sensitivity

Detlef Smilgies

I. Grazing Incidence

The first step to achieve surface

sensitivity is always to go to grazing incidence scattering geometry:

- At the critical angle x-ray beams

are confined to a penetration depth of about 100 Å, i..e

atoms deep in the bulk are not exited by the incident wave. This

results in a better signal-to-noise ratio.

- Furthermore, the electric field at

the is enhanced at the critical angle by a factor of up to 4, due to

the fact that incident and reflected wave fields are in phase. This

gives rise to an according signal enhancement.

Please refer to this link for detailed information.

II. Grazing Exit

By choosing grazing exit geometry the escape depth of x-rays from the

bulk is reduced - this is essentially the time-reversed argument from

part I.

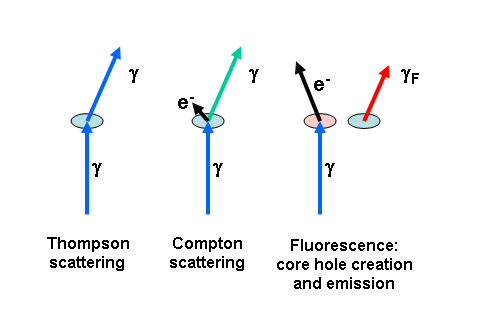

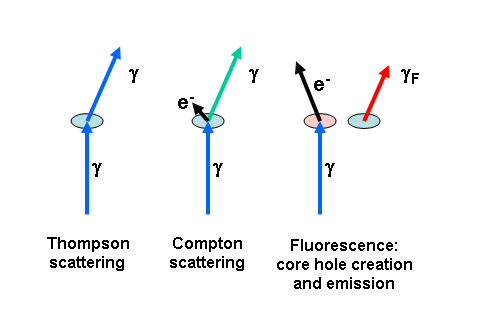

III. 90° Scattering

Geometry

By placing the detector in the direction of the

polarization vector of the incident beam, dipole scattering is strongly

reduced. This way both elastic diffuse scattering (Thompson scattering

from defects) and inelastic diffuse scattering (Compton scattering) are

minimized, again enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio. For an x-ray

fluorescence event, the memory of the incident beam polarization is

lost, and fluorescent radiation is unpolarized.

IV. Conclusion: Optimum Scattering Geometry

By orienting the sample horizontally and the fluorescent detector in

the horizontal plane, all three conditions I - III can be fulfilled

simultaneously. This scattering geometry can be achieved on a vertical

four-circle diffractometer with an additional fixed arm to support the

energy-dispersive detector. This way, the usual point detector can be

used for taking the reflectivity curve while the fluorescence signal is

recorded simultaneously. Another advantage of this geometry is, that

this way the surface is well adapted to the incident beam profile with

its narrow vertical width, whereas the full horizontal beam can be used.

V. Signatures of

Surface and Bulk Scattering

If the fluorescing atoms are located on the surface, the fluorescent

yield as a function of grazing angle should look like a Vineyard

function with the characteristic enhancement at the critical angle.

If the fluorescing atoms are located in the bulk (bulk impurities) the

fluorescence yield follows the penetration depth

curve. Because

of total external reflection, the penetration depths changes rapidly

while scanning through the critical angle and results in a distinct

angle dependence. If we make the simplifying assumption that we have a

constant density

of scatterers r within a layer of thickness L, then we get a simple expression for the scattering

intensity.

If there is a doping profile of impurities in the surface-near region

or if we have a well-defined thin film,

analysis is more involved, because interference effects within the wave

fields have to be accounted for in a quantitative analysis [see: de

Boer, PRB

44, 498 (1991)]. Again, angular scans through the critical

angle are combined with fluorescence measurements. This technique to

determine impurity or doping

profiles has been termed Total Reflection X-ray Fluorescence (TRXRF)

and is of importance for semiconductor industry.

VI. Detector

Choices

For incident beam energies below the Ge K-edge (11.1 keV) a Ge detector

is a good choice. Above this energy, a Si-Li detector is more suitable

detector, avoiding the Ge escape peak. A Ge detector has the highest

sensitivity due to its high stopping power. Both Ge and Si-Li detectors

have a relatively large active area, and apertures can be adjusted to

obtain good signal levels and good signal-to-noise.

Both Ge and Si-Li detectors have a rather limited maximum count rate of

about 10,000 counts per second, before they reach saturation. For more

intense scattering target, e.g. deposition of multiple monolayers, a

PIN-diode based detector or a Si drift diode based detector may be a

better choice. These detector have a small active area, but allow

higher count rates (up to 300,000 counts per second for a Si drift

diode).

All of the mentioned detectors feature an energy resolution of 150 to

250 eV. Using a multi-channel analyzer, fluorescence events over a

large energy range can be recorded simultaneously. This energy range is

limited by the incident beam energy (atoms need to be excited) and on

the low-energy side by the transmission of windows and flight paths

(the low-energy cutoff is typically at about 3 keV, unless special

measures are taken).

For higher resolution requirements, a crystal analyzer would be needed.

There are high-efficiency focussing analyzer designs with a resolution

of a few 10 eV. A crystal analyzer can also collect a range of energies

when combined with a linear detector.